Former Bulls top pick Orlando Woolridge dead at 52

by Sam Smith

Posted on Jun 1

The contents of this page have not been reviewed or endorsed by the Chicago Bulls. All opinions expressed by Sam Smith are solely his own and do not reflect the opinions of the Chicago Bulls or their Basketball Operations staff, parent company, partners, or sponsors. His sources are not known to the Bulls and he has no special access to information beyond the access and privileges that go along with being an NBA accredited member of the media.

Orlando Woolridge was “O,” both in uniform number and in exclamations.

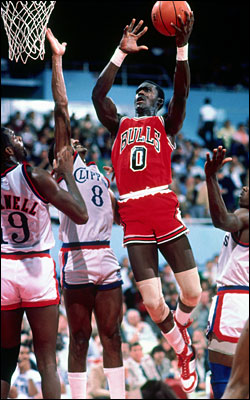

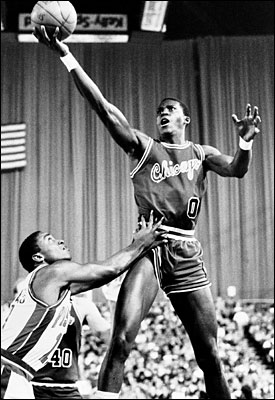

There was the big O in “wOw” in seeing the talent that led Notre Dame to its greatest basketball era ever, and the astounding “Oh my gosh” dunks that had the Bulls 1981 No. 1 draft pick competing in the first two NBA dunk contests with Julius Erving, Michal Jordan and Dominique Wilkins.

There was the one-one-one ability that left you gasping, “Oh!” that enabled him to beat just about anyone to the basket with double pump dunks that led him to average as much as 25 points per game in an NBA season.

There was the one-one-one ability that left you gasping, “Oh!” that enabled him to beat just about anyone to the basket with double pump dunks that led him to average as much as 25 points per game in an NBA season.

There, of course, was the sadness of his Oh so many demons that led him to be suspended for violating the league’s drug policy and even a theft arrest earlier this year.

And then there was the final, “Oh, no!” late Thursday when Woolridge back home in Louisiana died of heart disease at just 52.

“Maybe one of the biggest (wasted potential) in NBA history,” said Mychal Thompson, a teammate with the Lakers in the late 1980’s. “He was a guy with a great attitude on and off the court in spite of his demons. He was the first version of Amar’e Stoudemire, a 6-9 version of Michael Jordan and Clyde Drexler. That’s how athletic he was. If not for the addiction, there was a potential there to go through the roof.

“He was a hard worker off the bench, a great attitude,” recalled Thompson, a onetime No. 1 overall pick and now a highly regarded Los Angeles sports broadcaster. “That team was 11-0 going into the Finals. Then Magic (Johnson) and Byron (Scott) got hurt. Barring those injuries, he’d have been a champion. It’s a big loss.”

Perhaps that in some ways summed up the too short life of Orlando Vernada Woolridge, a popular, outgoing small town kid from Louisiana who maybe wanted to be liked and to please a bit too much, and it may have taken him down some of the more dangerous blind alleys the glamour of pro sports has and mostly tries to avoid.

“He was a great teammate,” recalled Isiah Thomas, who played with Woolridge in Detroit in the early 1990’s. “A fun loving guy, great sense of humor. He wasn’t confrontational at all. Just a guy you liked being around to talk about things.”

Friends, former teammates and opponents Friday remembered Woolridge fondly as a great talent who never achieved the fame perhaps promised, but who always was welcoming with an inviting smile.

“Just very sad,” said Rod Thorn, the Bulls general manager when Woolridge was drafted out of Notre Dame with the No. 6 pick in the first round. “My remembrance always was a guy with a smile, very pleasant to be around, a fun guy, upbeat and happy who had a long career with some outstanding years.”

That included four times averaging more than 20 points per game (16 for his career) to rank among the league’s best scorers in perhaps the greatest era in NBA history. Though it started in South Bend in the 1977-78 season when Notre Dame had its only Final Four team in Woolridge’s freshman season to the disappointing Danny Ainge dash to knock them out of the Sweet 16 in 1981 before Woolridge had the NBA scouts drooling.

“I’ve got really nice memories of Orlando,” said Bulls executive vice president John Paxson, who was a teammate of Woolridge’s at Notre Dame and with the Bulls. “A real gregarious guy with a wealth of talent and ability. With his talent and athleticism, he was a very difficult matchup.

“Back then, without the shot clock and the game at a slower place, he really wasn’t able to showcase a lot of what he could do,” said Paxson, noting Woolridge’s 10.6 collegiate scoring average. “But I remember a lot of times, we’d just throw the ball to the square and Orlando would go and get it. He was that athletic.

“In college, without the clock, the coaches back then had control of the game,” said Paxson. “Teams were playing in the 50’s and 60’s (points). And there was a lot of shot distribution with the players we had (Paxson, Kelly Tripucka, Tracy Jackson and earlier Bill Laimbeer and Bill Hanzlik). He wasn’t even the player he’d become. He could get to the basket and then he started to make that mid range fadeaway. He was such a good guy, but at some point he had to battle a lot of personal things, which is part of being human. He had demons like many of us do, but at his core, he was a really good person, friendly, smiling a lot.”

There’s no need to make excuses. But it was a difficult time for many around the NBA. The Suns would go through a drug scandal that would bring in law enforcement. The Rockets would face numerous expulsions after being in the Finals. The NBA was supposedly saved by Larry Bird and Magic Johnson in 1979. But the truth was the struggle went into the 1980’s to the point the players agreed to a salary cap in 1983 with several teams facing bankruptcy.

And Woolridge came to the Bulls desperate for success but with their own demons. Management was a mess with seven owners involved in most everything but basketball. There was talent with Artis Gilmore and Reggie Theus. But there was turmoil. The Bulls had lost Johnson in the 1979 lottery and drafted David Greenwood No. 2. They’d go to the playoffs in 1981, but before Woolridge’s rookie season was over coach Jerry Sloan was fired.

Attendance was poor, so ownership low balled Woolridge and he held out, producing ambivalence among the fans.

Attendance was poor, so ownership low balled Woolridge and he held out, producing ambivalence among the fans.

“The first basically 50 games he didn’t get to play because of the holdout,” said Thorn. “But he began to show potential when he got in there. We took him on potential as he’d only averaged about 10 points at Notre Dame. He was a jumper, runner, strong body, though not really a rebounder. He had some great scoring years, but then there’d be rumors about him.”

Woolridge fell in with the wrong group, though they represented much of the roster. There was Quentin Dailey, who died two years ago, Mitchell Wiggins, Ennis Whatley, Wes Matthews, all players who had issues. Michael Jordan, a rookie in 1984, said he’d walk by teammates’ rooms on the road with the thick odor of smoke, apparently from marijuana, wafting under the door.

It was the thing to do around much of the NBA at the time, if not in many major sports, and Woolridge was always a guy who wanted to get along and be liked.

“A good man with an infectious personality, he’d embrace you and make you feel important,” recalled Billy McKinney, a Bulls teammate and later a Pistons executive who helped bring Woolridge to Detroit. “That was a quality I admired about him. He had a lot of responsibility coming to that team at that time. He really was ahead of his time as that hybrid forward who could beat the big guys at four and outjump the quick guys at three. He was such a perfect physical specimen he never had to lift a weight. When he went to play with the Lakers and was around a stronger group of players it was good for him. You wonder what would have happened if those guys were around him when he started.”

Woolridge also got caught in the changeover to new Bulls ownership in 1984 with Jordan becoming the focus of the franchise. Woolridge would lead the team in scoring the season before Jordan arrived and in Jordan’s second season when he was injured, Woolridge averaging 22.9 that season. Woolridge had one more Bulls season, averaging 20.7.

“Good guy,” recalled Charles Oakley, a Bulls teammate. “A lot of things happen in life. You’ve got to fight. But he always kept a smile on his face. I always had a good time playing with him, a real flier and jumper.”

But then Woolridge was flying as a free agent to the New Jersey Nets, another losing team. The Bulls acquired a future first round pick they’d eventually use to draft Stacey King.

“A very nice person,” said Bulls general manager Jerry Krause. “But when I took the job he was one of the guys we had to change. He had some problems and was more an individual player. The team concept wasn’t there.”

Woolridge moved onto the Nets, where he eventually was suspended beginning an NBA odyssey to the Lakers, Nuggets (where he averaged 25.1 under Paul Westhead, one of his many Bulls coaches), Pistons, Bucks and 76ers and retiring from the NBA after the 1993-94 season.

Woolridge then went to play in Italy and got that elusive title playing in Bologna and for Mike D’Antoni. He returned to the NBA as a coach in the WNBA and also coached in the minor league ABA.

”He was always great to me,” said McKinney. “When he was playing in Italy and I was going there to scout he took me around and made sure everything was taken care of, took my wife and me on a tour of Rome one day. It was something I really appreciated.

“My memory of him was a guy always with a smile on his face no matter what was going on,” said McKinney. “It’s stunning to hear even though I knew he was sick. I’d see him at Tennessee where his son was playing. We’d get together, chat and kept in touch. It’s really sad to hear.”

Perhaps Woolridge’s NBA legacy wasn’t what it could have been, and his personal problems were a disappointment. But Woolridge has left a classic legacy. His son, Renaldo, also Gale Sayers’ godson, is graduating from Tennessee with a sociology degree after playing four years. Older son Zach graduated from Princeton and daughter Tiana plays volleyball at Princeton.

GOOdbye, O. Rest in peace.

NBA.COM is part of the Turner Sports and Entertainment Digital Network.

NBA.COM is part of the Turner Sports and Entertainment Digital Network.